First of all, I don’t blog nearly as often as I should. If my records are accurate, this is the first official blog post I have published on the Leader of Learning blog since January 30, 2018. However, I am trying to turn over a new leaf – two new leaves, actually. First, I would like to blog again (semi-) regularly. Part of the reason I began the Leader of Learning Podcast was to share content in a form that would not have me writing so much. It’s not that I hate writing, I actually enjoy it. As a doctoral candidate writing a dissertation, though, I figured I do enough of it already. Second, I would like to read more. I am constantly accessing great content to grow myself as an educator and as a leader. Much of this content is consumed through audio as podcast episodes and audiobooks. With a fourth-grader and a kindergartener at home now, I am planning to make family reading time a nightly occurrence and figured I would rather go back to reading “books” on my Kindle device.

Well, on a whim, I decided this past weekend to grab my Kindle from out of the small pocket in my backpack and search the Kindle Lending Library for a great free read. After not finding anything good right away in the “Education and Teaching” category, I searched “Business and Money.” Not far into my search, I found “The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead Forever” by Michael Bungay Stanier. Little did I know at the time, this book is actually ranked #3 in “Business Mentoring & Coaching” and #5 in the “Business Leadership” and “Business Management” subcategories in the Kindle Store. Likewise, little did I know then that this book would have such a major impact on me and the way I approach my job and my colleagues.

Here’s the book:

The book was easy to read and laid out in sections which corresponded to seven questions that author Michael Bungay Stanier thinks are THE questions to ask in leadership and coaching sessions. Here are the seven essential questions:

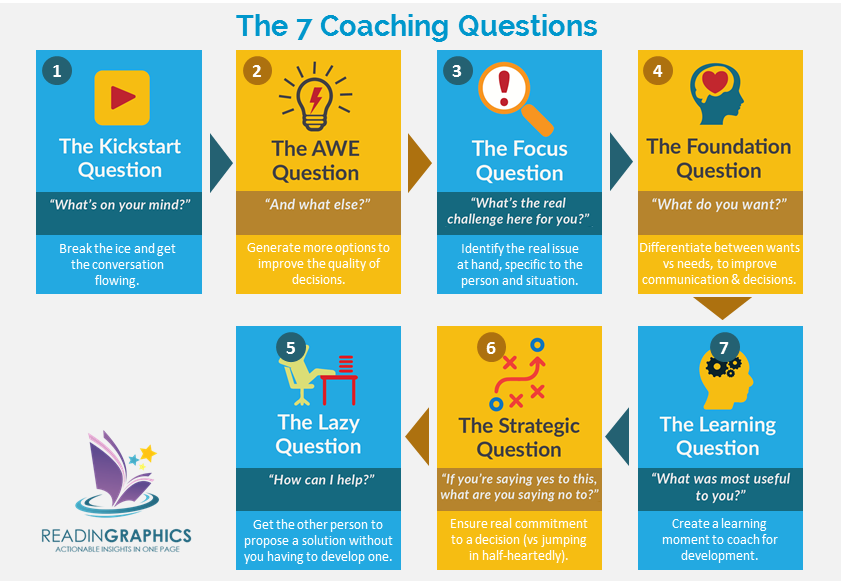

- The Kickstart Question—“What’s on your mind?” This is the opening question to help you break the ice and get the conversation flowing.

- The AWE Question—“And what else?” This question helps you to uncover and generate new options or possibilities while overcoming the urge to give premature advice.

- The Focus Question—“What’s the real challenge here for you?” The first 2 questions are likely to get the other party talking and sharing. Yet, they’re probably not highlighting the real problem. This question helps you to identify the underlying issue to be addressed.

- The Foundation Question—“What do you want?” This question helps people to gain clarity on what they want, which improves communication and decision-making.

- The Lazy Question—“How can I help?” This question is “lazy” because it gets the other person to propose a solution without you having to develop one.

- The Strategic Question—“If you’re saying yes to this, what are you saying no to?” This question gets the other person to consider if he/she is truly prepared to commit to a decision, rather than jump in half-heartedly.

- The Learning Question—“What was most useful to you?” Coaching for development (focuses on the people handling the issues) is more impactful than coaching for performance (tackling specific challenges and putting out day-to-day fires). This question allows you to create a learning moment to coach for development, in addition to coaching for performance to solve the problem.

Here’s an amazing printable graphic of the same 7 questions made by READINGRAPHICS:

Aside from these powerful questions to ask the teachers whom I coach, there were a couple of other ideas in the book which resonated with me. First was this quote:

“When you build a coaching habit, you can more easily break out of three vicious circles that plague our workplaces: creating overdependence, getting overwhelmed and becoming disconnected.”

As an instructional coach and someone who has been in school leadership roles throughout much of my educational career, I have all too often seen these “vicious circles” have such negative impacts on educators. The one that speaks to me most, however, is creating overdependence. As a parent and former classroom teacher, I know full well that when kids rely too much on adults, they are not really learning for themselves. It is only when they can fully internalize new learning and can replicate it on their own that they have truly learned. Additionally, reflecting on their learning is a crucial step toward internalizing it. Similarly, teachers need to internalize their own professional learning. It is not enough for teachers to rely on their instructional leader(s), coach or administrator, for the answers to the challenges they face in their classroom. Rather, they must be “in the driver’s seat” of their own development.

“Coaching can fuel the courage to step out beyond the comfortable and familiar, can help people learn from their experiences and can literally and metaphorically increase and help fulfil a person’s potential.”

Another aspect of this book that stood out to me was the descriptions of the difference between “coaching for performance” and “coaching for development.” In the book, coaching for performance is explained as “addressing and fixing a specific problem or challenge. It’s putting out the fire or building up the fire or banking the fire. It’s everyday stuff, and it’s important and necessary.” The book explains coaching for development as “turning the focus from the issue to the person dealing with the issue, the person who’s managing the fire.” I’m assuming if you are reading this, you are probably an educator who wants to make an impact on other educators and/or students. You must decide for yourself which one of these types of coaching you wish to pursue. If you’re like me, you will likely choose coaching for development. Instead of simply dealing with issues as they arise, this type of coaching should allow for an ongoing development process that is continuous and logical. Sure there will be issues and challenges that must be dealt with along the way, but they will merely serve as the “reason” or “trigger” (read the book to understand these terms better as they fit into the coaching process) which inspires a new development.

What are my personal takeaways from reading this book and heading into a new school year in which I will be supporting classroom teachers? First and foremost, the title of the book says it all. I want to SAY LESS, ASK MORE, and CHANGE THE WAY I LEAD… and COACH. I want to make coaching less about me being a “rescuer” (again, read the book to find out how this term fits into the coaching process) and help to eliminate the overdependence teachers may have of me to offer too much of my own thoughts, ideas, and advice. I want the teachers I support to internalize their own professional learning and to partner with them to do what they believe is right to grow themselves and their students.

In other words, I want the teachers to be the ones who drive their own development as an educator. This is a concept that I have considered throughout my time as an instructional leader. However, sometimes it’s easy to get “sucked in.” When you notice a teacher struggling in a certain area of their instruction, or that students are bored in class, or student outcomes are not what they should be, you have a tendency to want to come to the rescue with your own advice and draw from your own experiences. I vow to avoid that at all costs from now on. I think if I can do that, it will not only benefit the rapport I have with each teacher, but it should also help the teacher grow faster and farther.

I know I just said I would refrain from giving away too much of my own advice but I will share this advice with you: ask more. As author Michael Bungay Stanier wrote in the book, “Ask one question at a time. Just one question at a time.” This way you may just be reaching this ultimate goal of coaching and leading others:

“You’re not telling them or guiding them. You’re showing them trust and granting them the autonomy to make the choice for themselves.”